Element of Water

H₂O A molecule formed by the combination of two Hydrogen atoms with one Oxygen atom. A liquid considered colorless and tasteless. Covering 60% of the human body and 71% of the Earth’s surface, water is one of the very first things we search for when exploring the possibility of life on other planets. Yet where our Earth—once a ball of fire that cooled over time—first found its water is still debated. Some scientists believe water formed during Earth’s creation, while others claim it was brought here by objects like comets or asteroids. In short: its source is disputed, but its presence is indisputable.

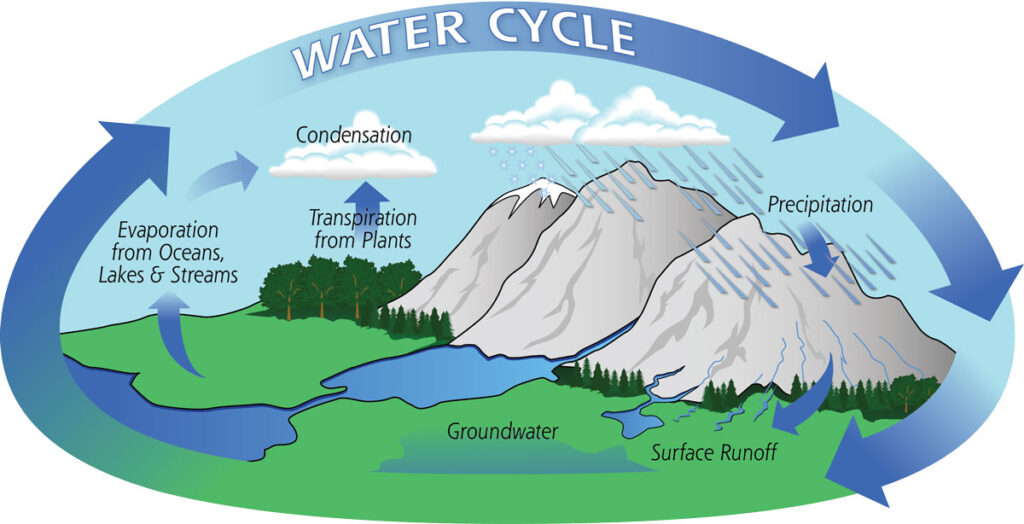

Water is in constant transformation, appearing to us in different forms at different stages of its cycle. Pure water is rarely found in nature; usually it interacts with its environment, and its content changes as a result. In its purest state, it rises into the atmosphere as vapor. Yet even there it interacts with dust and various gases. Meeting a mass of cold air, it condenses and falls as rain. When it falls at high altitudes, it flows downward in accordance with gravity. Along its course, part of it seeps underground to continue its journey below, while the rest flows across the surface until it reaches its final destination: the sea. On this journey, it gives life wherever it passes and gathers elements along the way.

At this point we may ask (and rightly so): If the water that flows through rivers is not salty, why are the seas—where all rivers eventually flow—salty? (Let’s pause a moment for those who wish to answer.) Ready? Let’s continue: Rivers carry minerals and salts to the sea. The amount in any given unit is too small to notice, but over millions of years these salts accumulate in the still basins of the oceans.

In the seas, water evaporates with heat from the sun. The cycle completes. (Here, of course, one could ask: “Then why doesn’t the salt concentration of the seas increase endlessly?” I’ll leave that as your homework. Hint: precipitation and sedimentation.)

Because water is constantly before our eyes, we sometimes forget to give it the value it deserves. Yet compared to gold or silver—rare substances on Earth that we ascribe material value to—water contains far more remarkable and unique qualities.

So let us begin our exploration of the water element from this point:

Our Water

1. Volume

Water has a volume, and that volume remains constant—meaning water cannot be compressed. Being a liquid, it has no fixed shape; it is fluid, and takes the shape of the container or environment it occupies. But this does not change its volume.

The water element, because of this property, is associated with emotions. Emotions too can take shape according to a relationship, an event, or a situation, but their basic volume—that is, a person’s emotional capacity—is fixed.

Emotions fill us, but they do not fill everyone equally. Since their volume cannot be compressed, the only way to hold more is to expand our inner space.

When our inner reservoir is small, we do not leave enough room for emotions. No matter how much rain falls, the amount of water we can store remains limited. When emotions are lacking, our connection to life becomes more superficial. Empathy becomes harder, and we struggle to understand and interpret life.

We have witnessed small puddles drying out on hot summer days. Likewise, lack of love and emotion leads to the desertification of our inner life.

When an external force is applied to water, it transmits that pressure equally in all directions. The emotions that fill us behave the same: when they are pressed upon, the force spreads throughout our body.

If our emotional reservoir is small, exposure to intense emotions creates overwhelming pressure inside us, affecting the whole body.

In the opposite case—when our emotional reservoir is nearly bottomless—the load of emotions becomes excessive. This burden may grow so heavy it paralyzes us. Since this inward current creates over-identification with the world around us, we may struggle to distinguish our own emotions from those of others.

Too many emotions make both recognition and control difficult. Even fuel tankers have specially designed interiors to ensure safety.

Emotional reservoirs that are too large can be dangerous both to us and to others.

And the danger does not come merely from carrying such a reservoir. Oceans themselves are immense bodies of water, yet much of them remain unexplored, because the conditions they hold are inhospitable to humans. At extreme depths, the pressure is so great that even with advanced submarines, access is impossible. Likewise, an overly deep emotional reservoir contains such pressure—closed to healthy human access, and full of hidden dangers.

Divers who descend to great depths encounter a condition called nitrogen narcosis, a temporary state of mental fog caused by breathing nitrogen under high pressure. It has a narcotic effect on the nervous system: weakening consciousness, impairing judgment, blurring vision, destabilizing mood.

Those who dive into excessive emotional depth can experience something similar: a kind of “emotional narcosis.” The mind grows clouded, stuck in the past and nostalgia, reactions become erratic, melancholy takes over, and the return to the surface becomes impossible.

Suyun ikinci özelliği en benzersiz özelliğini de içerir:

2. Temperature

Temperature determines both the form and the fluidity of water. Under normal conditions, water freezes at 0 °C and becomes ice. (Here its most unique property emerges: unlike most substances, water expands when it loses heat and turns solid.)

Between 0 °C and 100 °C it remains liquid. Above 100 °C it turns into gas and becomes vapor. Temperature not only changes water’s form, but also its behavior and effects.

The temperature of our emotions likewise determines their form and fluidity. As they cool, transmission becomes difficult. Communication begins to break down. If cooling continues, emotions harden, and eventually freeze. Just as frozen water expands, frozen emotions expand and damage the body. Once freezing begins, continued loss of warmth spreads the effect further.

To understand this, we must also remember the transformation of form. Say water freezes and cools to –50 °C. If we begin heating it again, no change is observed at first. It must reach 0 °C before it can return to liquid. Emotional numbness carries the same risk: a little warmth only raises its temperature without altering its form. For change to be seen, it must cross a critical threshold—the freezing point. –50 °C ice and –1 °C ice are both ice, but they are vastly different. The absence of visible change does not mean nothing is happening.

Another misconception is that water only evaporates by boiling. In truth, water evaporates at all temperatures; heating merely accelerates the rate.

When emotions heat up, the process is similar: they evaporate faster. Boiling is when vaporization occurs throughout the entire body of water. Water, once liquid in a fixed volume, expands in gas form. Its atoms, with more energy, press harder against the container. (This is precisely the environment created in a pressure cooker.)

When emotions inside the reservoir reach boiling, they expand and press against us. Excessive emotional pressure can harm both us and those around us. Managing and directing them becomes very difficult.

In pressurized environments, the weakest point on the surface is at risk. Returning to the pressure cooker: the joint between lid and pot is more vulnerable than the strong base. If the sealing rings are worn, leaks begin. The weakest point cannot withstand the pressure and bursts.

The same is true in us: when emotional pressure rises, the most worn and vulnerable parts of our body and mind face great risk. If heating continues, explosion becomes inevitable.

The pressure cooker’s whistle has two purposes: to signal the rise of pressure, and to release excess. Yet opening the whistle suddenly in an over-pressurized pot makes matters worse. First, heat must be reduced; only then can safe release begin.

So it is with our emotions: being aware of our pressure is essential. But rushing to vent emotions at the peak of their pressure can be dangerous. The first step must be to reduce the heat, let the pressure reach a manageable level, and only then release.

3. Bed (Channel)

The bed gives direction to water. But the process is mutual: the bed is shaped by the movement of water, while also guiding its flow. The bed is water’s boundary, enabling its movement. A wide bed slows the current; a narrow one speeds it up.

Emotional flow, too, needs boundaries—emotional channels—in order to move.

When the emotional channel is weak, the first rise in emotions causes floods. The flow cannot reach its destination. Boundaries in relationships dissolve, leading to emotional chaos.

When the channel is too wide, transmission slows, and emotions dissipate before reaching their goal.

When the channel is too strong, the flow is overly restricted. Excessive limitation suppresses emotions. When control grows too rigid, flow stops, water stagnates. Communication ceases, leading to withdrawal.

Water and its bed constantly shape one another. If the bed is permeable, water seeps underground and its discharge lessens. With little slope, the river meanders in curves. After flowing past resistant beds, water erodes softer soils, carving waterfalls. When the water carries too much load, it gradually fills its bed, shifts course, even forms deltas.

Emotions are just as varied. Moreover, the same emotions differ from person to person, and even within the same person at different times. Each emotional flow creates a different effect, and if prolonged, the effect becomes more intense and lasting.

But the bed changes emotions too. An obstacle-free channel ensures a calm flow, while a rugged one foams the waters. The inner structures we build shape our emotions and their movements.